Advanced Medical Therapies for IBD

Advanced Medical Therapies for IBD

February 17, 2026

Issue 02

Mentoring in IBD is an innovative and successful educational program for Canadian gastroenterologists that includes an annual national meeting, regional satellites in both official languages, www.mentoringinibd.com, an educational newsletter series, and regular electronic communications answering key clinical questions with new research. This issue is based on the presentation made by Dr. Vipul Jairath, at the 26th annual national meeting, Mentoring in IBD XXVI: The Master Class, held in Toronto on November 14, 2025.

Introduction

The objectives of this presentation were to review the data for the use of dual therapy, the simultaneous use of two advanced therapies in IBD, also referred to as advanced combination therapy [ACT]. It also included discussion on the clinical considerations when using ACT and explored future concepts of ACT.The objectives of this presentation were to review the current treatment armamentarium for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the best evidence for positioning of advanced therapies, and combination therapies as an emerging treatment strategy. Overall, the therapeutic landscape in IBD has evolved considerably, from the pre-biologic to the biologic era, with current therapies targeting several mechanisms of action,1 such that the field has become a “maze”.

Efficacy of Current IBD Agents

There are several drug classes currently available for the treatment of IBD, including anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, anti-integrins, interleukin inhibitors (IL-23), Janus Kinase inhibitors (JAKi), and S1P receptor modulators. Across classes and within classes, these drugs are considered effective and safe for the treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC).

Anti-TNF agents date back to the mid-1990s but are still relevant today as the only therapies with clear evidence of efficacy in perianal CD. Anti-TNFs are also favoured for use in post-operative prevention,2 for extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs), and remain a cornerstone for acute severe ulcerative colitis (ASUC). However, anti-TNF agents have limitations including potential development of antibodies3 and varying treatment responses.4,5

Vedolizumab, an anti-integrin, is uniquely indicated for IBD, and is considered a first-line option for UC, with demonstrated superiority to adalimumab.6 Vedolizumab is less commonly used in CD, despite available data supporting its use in post-operative prophylaxis7 and in early CD among bio-naïve patients.8 Vedolizumab is the first biologic to show benefit for transmural healing.9 Furthermore, preliminary results from the VERDICT trial in a bio-naïve population show achievement of disease clearance (endoscopic, histological and symptomatic remission) in two thirds of patients following a year of therapy.10

There are three IL-23 inhibitors currently available in IBD, guselkumab, risankizumab, and mirikizumab, with extensive efficacy and safety data showing little evidence of clinically meaningful differences among them. Data suggest that IL-23 inhibitors are the preferred therapy for people who do not respond or lose response to anti-TNF therapy.11 Findings from pivotal trials12,13 clearly support that IL-23 inhibitors are superior to ustekinumab in CD. Overall, IL-23 inhibitors have reported high efficacy rates for endoscopic healing in both CD and in UC.14

JAKi (tofacitinib and upadacitinib) have demonstrated the significant benefit of rapid response.15,16 In addition, post-hoc trial analyses have shown JAKi may be beneficial for fistulas in CD.17 JAKi should also be considered the as first-line treatment for EIMs given their multiple other indications, such as rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, atopic dermatitis, etc. Furthermore, the use of JAKi in ASUC is being explored.18

Lastly, S1P receptor modulators can be considered a first-line therapy option, particularly for patients who prefer oral therapies. S1P receptor modulators have demonstrated clinical remission and endoscopic improvements in UC compared to placebo.19 In addition, S1P receptor modulators are the only agents with evidence supporting their use for proctitis.20

IBD Treatment Safety

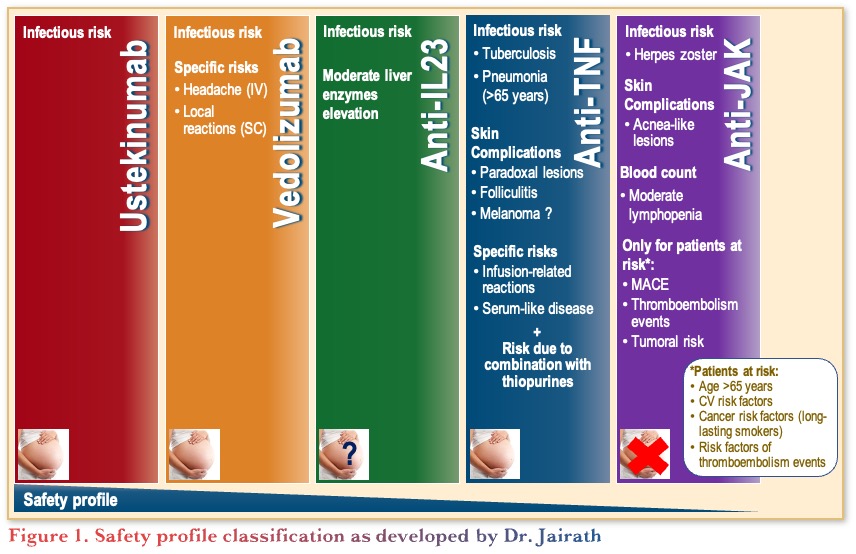

Classifying and comparing the safety profiles of IBD therapies is challenging, as shown in Figure 1. PYRAMID, a post-hoc registry analysis, found that patients who responded to anti-TNF therapy have fewer infections than non-responders.21 The findings reinforce that active disease is a risk factor for infection. Thus, safety is partly dependent on efficacy.

A meta-analysis compared JAKi to anti-TNF therapies in immune-mediate inflammatory diseases (IMIDs). Across ~800,000 patients, no differences were observed between JAKi and anti-TNFs for infections, malignancy, and major adverse cardiovascular events across all IMIDs.22 A slightly higher risk for thrombosis was reported with JAKi, driven by the rheumatoid arthritis population,22 showing that overall JAKi have a comparable safety profile to anti-TNFs.

Thus, when discussing safety with patients, it is important to emphasize that effectively treating active disease with proven IBD therapies is itself a key safety component.

Positioning of Drugs

Drug positioning should be guided by a personalized treatment approach that recognizes patient heterogeneity. Selecting therapy remains the art of medicine, requiring considerations of efficacy, safety, patient preference, cost, and reimbursement. To support decisions, physicians can draw on head-to-head trials, network meta-analyses, and real-world evidence.

First-line therapies in CD

Several options are available for first-line therapies in CD with recent comparative data to help guide selection. Specifically, in a head-to-head trial comparing adalimumab to ustekinumab in moderate-to-severe CD, no differences were observed in clinical remission and endoscopic response.23 Three trials, VIVID,24 SEQUENCE,13 and GALAXI,12 each evaluated IL-23 inhibitors versus ustekinumab. Risankizumab13 and guselkumab12 demonstrated superiority to ustekinumab, while mirikizumab showed similar efficacy; although it should be noted that ustekinumab performed better in the VIVID trial.24 Taken together, the three IL-23 inhibitors show consistent efficacy across studies, supporting IL-23 inhibitors as a first-line class over ustekinumab in CD.

Aligned with this, several network meta-analyses show consistent findings, whereby risankizumab is ranked highest, followed by infliximab,25 potentially highlighting a broader pattern in class-level performance. In analyses focused on endoscopic outcomes, JAKi and IL-23 inhibitors were the most efficacious.26

To note, there is also extensive real-world evidence with a notable example of the UK IBD BioResource analysis of 15,000 patients across 106 hospitals. Results show similar efficacy for infliximab, adalimumab, and vedolizumab in luminal CD, while infliximab was superior for perianal CD.27 Two caveats include, the study was conducted over 5 years ago and vedolizumab and ustekinumab were restricted to second-line use.

Second-line therapies in CD

IL-23 inhibitors are preferred options for second-line therapy after anti-TNF failure.17 Additionally, post-hoc analyses show that the JAKi upadacitinib is favoured for achieving clinical remission, regardless of the number or type of previously failed drugs.17 As such, for patients with biologic failure, IL-23 inhibitors or JAKi should be considered leading second-line options.

Switching between anti-TNF agents remains an option in cases of anti-TNF sensitization. However, if a patient has primary or secondary loss of response without sensitization, switching to a different therapeutic class is recommended.28 The recommendation to switch out of class is further supported by evidence from the UK IBD BioResource dataset.27.

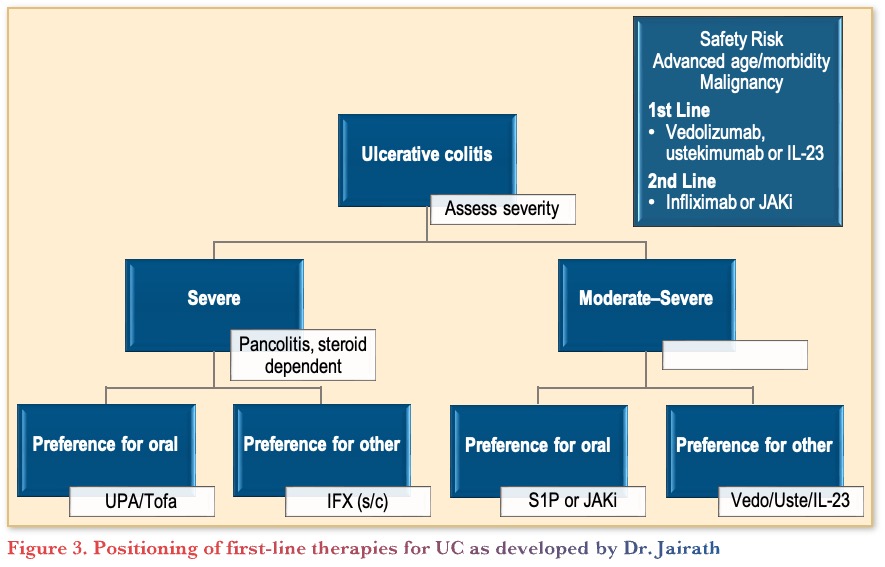

First-line therapies in UC

Comparative data in UC are limited, with one head-to-head trial showing that vedolizumab outperforms adalimumab.6 In a network meta-analysis, upadacitinib ranked highest for endoscopic improvement, both for induction and maintenance, although IL-23 inhibitors were also highly ranked across outcomes.29 Furthermore, real-world evidence from the UK IBD BioResource cohort, suggests that vedolizumab has the best treatment persistence, followed by infliximab and other anti-TNFs.27.

Advanced Combination Therapy

To date, there are no approved indications for combination therapy, whether combining two biologics, a biologic and a small molecule, or two small molecules.30 As single agents, remission rates often plateau at 50–60%, thus the hope is that combination therapy may be a strategy to break through this therapeutic ceiling.

A 2007 proof-of-concept study31 that analyzed infliximab in combination with natalizumab showed non-significant trends in favour of combination therapy without any new safety concerns. More recently, combination therapy with an IL-23 inhibitor plus anti-TNF therapy led to doubling of the endoscopic improvement rate (50% vs. 25%) compared to either monotherapy.32 A multicenter Canadian study was conducted across 1,012 centers with 105 patients with refractory IBD, uncontrolled IMID and uncontrolled EIMs. The study evaluated cumulative rates of clinical and endoscopic response, and serious infections.33 At 12 months, the clinical and endoscopic responses exceeded 60% and remission rates were around 30%, with 7% of patients experiencing serious infections. Negative predictors of response included long disease duration, perianal disease, and use of steroids.33

Regarding which agents can be combined, hypothetical uncertainties remain around combining a JAKi with an anti-TNF or IL-23 inhibitor. However, the remaining possible combinations of therapeutic classes appear to be safe. Combination therapy can be considered for patients who have failed all other options and have a high-risk phenotype, such that the risk of suboptimal monotherapy outweighs the risk of combination therapy. Best practices, when considering combination therapy, are to consult with a multidisciplinary team, including surgeons, explore multiple therapeutic avenues, provide thorough patient counselling, and establish predefined criteria and timelines for evaluating treatment outcomes (e.g., reassess after 6 months).34

Algorithms for Positioning Treatment

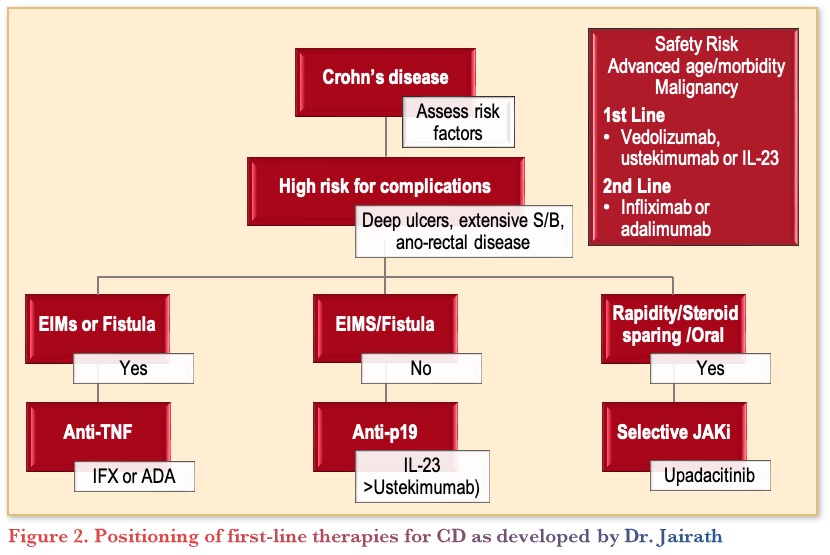

To determine first-line therapy for a patient with CD, the following pathway provides guidance, indicating the multiple factors that can be used to inform treatment selection (Figure 2).

To determine first-line therapy for a patient with CD, the following pathway provides guidance, indicating the multiple factors that can be used to inform treatment selection (Figure 2).

Ryan is an otherwise healthy 42-year-old electrician who was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) 4 years ago. He had a history of rectal bleeding for 5 years, initially attributed to hemorrhoids. Colonoscopy revealed inflammation to the mid sigmoid colon (Mayo 2). Fecal calprotectin was 1238 µg/g. He started oral and rectal 5-aminosalicylate (ASA) with some improvement observed in the bleeding and bowel urgency, but developed chest pain a week later. Ryan went to the emergency room (ER), was assessed with an electrocardiogram (ECG), which demonstrated non-specific ST segment and T wave changes; echocardiogram showed mild hypokinesis and a thickened myocardium. The diagnosis of myopericarditis was made.

Clinical Case

- Ryan is an otherwise healthy 42-year-old electrician who was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (UC) 4 years ago. He had a history of rectal bleeding for 5 years, initially attributed to hemorrhoids. Colonoscopy revealed inflammation to the mid sigmoid colon (Mayo 2). Fecal calprotectin was 1238 µg/g. He started oral and rectal 5-aminosalicylate (ASA) with some improvement observed in the bleeding and bowel urgency, but developed chest pain a week later. Ryan went to the emergency room (ER), was assessed with an electrocardiogram (ECG), which demonstrated non-specific ST segment and T wave changes; echocardiogram showed mild hypokinesis and a thickened myocardium. The diagnosis of myopericarditis was made.

Commentary

- Evidence supports 5-ASAs are generally safe

- Common side effects include gastrointestinal, cardiac, hepatic, musculoskeletal, pulmonary, renal, and reproductive, although the severity and risk can vary

- There are conflicting studies about the risk of renal side effects, but overall, they are considered very rare

- Annual check-ups are recommended

Case Evolution

The oral and rectal 5-ASA is discontinued given concerns this was associated with myopericarditis, and Ryan is provided budesonide enemas for induction of remission, which is well tolerated. Symptoms improve despite use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) for analgesia. You are aware a maintenance strategy for his UC is required, but he preferred to see if his symptoms return after he completed the 2 weeks of rectal steroids. Three months later symptoms return, infective screen is negative, and repeat fecal calprotectin is 1894 µg/g with Mayo 2 colitis to the mid transverse colon. A ‘pre-biologic’ work-up is completed..

Commentary

- There is no reason to contraindicate NSAID use among patients with IBD, but regular use is not recommended.

- There are several options for the next course of therapy in this case, including another course of steroids, azathioprine, S1P receptor modulators, JAKi, or anti-TNF.

- To determine which therapy to prescribe, gastroenterologists can take into account drug efficacy and safety, patient choice, lifestyle/convenience, and disease severity. Often patient preference for route of administration or a patient knowing someone on a specific drug are determining factors.

- To narrow down choice, it may be helpful to group therapies into like-categories (e.g., oral therapies versus injectable therapies).

- Cost/coverage may also influence the therapy decision.

- Among gastroenterologists, most would prescribe vedolizumab for this case. A few noted that given his occupation as an electrician, and that he is young, he may prefer oral medication, and thus would pick an S1P receptor modulator.

Case Evolution

After a discussion of effectiveness and safety of the options, Ryan chooses vedolizumab (anti-integrin) with intravenous (IV) induction and q2w subcutaneous (SC) injections. He responds well for 18 months but does not like the injections and states that attending infusions are too troublesome, so he wants to stop all medications. Further, he discloses that he fell at work 4 weeks ago, broke his leg and then had a ‘blood clot’ for which he has started blood thinners. He attributes the fall to feeling clumsy with tingling in his hands and feet and mentions his sister has a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. You arrange an MRI brain/spine and fortunately no demyelinating lesions are identified but early changes of sacroiliitis are noted, and bloodwork confirms he is HLA-B27 positive.

Commentary

- Gastroenterologists note differences in practice when it comes to IV versus SC injections. Some physicians will routinely offer SC and transition patients after induction therapy. However, many patients are resistant to changes in route of administration and will stick with IV, unless there is a question of convenience.

- Having IBD increases the risk of blood clots about 2-fold even if in remission, while active disease increases the risk of blood clots to about 10-15 times. Therefore, it is important to assess patient history and risk factors for thrombosis, consulting with a hematologist if possible.

- This patient also has spondyloarthropathy and with that in mind, a JAKi may be an important option given only JAKi and anti-TNFs have evidence to support efficacy for axial disease. Meanwhiie, IL-23 inhibitors have debatable efficacy for axial disease.

- He is also HLA-B27 positive, which is a poor prognostic factor for sacroiliitis, suggesting he may have more aggressive disease.

- In this case, gastroenterologists should work with a rheumatologist, neurologist, and hematologist, if possible, as his history of blood clots and family history of demyelination are important parts of the decision-making process.

Case Evolution

You both agree on switching to etrasimod (2mg oral daily) and this is well tolerated. His UC is under control but at the 12 month follow up, he states he has been diagnosed with diabetes, has been started on oral medications, and he has recurrent back pain. You have heard that etrasimod may predispose individuals to macular edema and you ponder what other options are available if his UC starts to flare. Unfortunately, he is back in your office 18 months later, reporting marked bowel urgency, tenesmus, and rectal bleeding. Flexible sigmoidoscopy demonstrates 5cm of Mayo 2 proctitis but mucosal healing above. He does not want to use any form of steroids as his diabetes has been harder to control and asks what other options he has as his proctitis symptoms are not compatible with working as an electrician in a crawl space.

Commentary

- The risk of macular degeneration is very low with estrasimod and as such would not influence clinical choices. Regardless, patients taking estramiod should be encouraged to have regular eye examinations.

- Overall, the biggest threat to any patient’s health is active disease and steroid overuse, which outweigh the possible risks of treatment.

- From a physician’s standpoint, treatment decisions often rely on recent clinical experience, as it can be a challenge to differentiate between all the treatment options.

References

- Vieujean S, Jairath V, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Understanding the therapeutic toolkit for inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;22(6):371–94.

- Regueiro M, Feagan BG, Zou B, et al. Infliximab reduces endoscopic, but not clinical, recurrence of Crohn’s disease after ileocolonic resection. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(7):1568–78.

- Bongartz T, Sutton AJ, Sweeting MJ, et al. Anti-TNF antibody therapy in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of serious infections and malignancies: systematic review and meta-analysis of rare harmful effects in randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006;295(19):2275–85.

- Remicade [package insert]. Horsham, PA: Janssen Biotech, Inc; 2013.

- Humira [package insert]. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie, Inc; 2013.

- Sands BE, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(13):1215–26.

- D’Haens G, Panaccione R, Higgins PDR, et al. Vedolizumab to prevent postoperative recurrence of Crohn’s disease (REPREVIO): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;10(1):26–33.

- D’Haens GR, Löwenberg M, Baert F, et al. Vedolizumab in early and late Crohn’s disease (LOVE-CD): a phase 4 open-label cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2026;11(1):12–21.

- Rimola J, Colombel JF, Bressler B, et al. Magnetic resonance enterography assessment of transmural healing with vedolizumab in moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: feasibility in the VERSIFY phase 3 clinical trial. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2024;17:9–23.

- Jairath V, Zou G, Adsul S, et al. DOP050 Target achievement after 48 weeks of vedolizumab treatment in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: an interim analysis from the VERDICT trial. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;19(Suppl 1):i180–81.

- Atreya R, Neurath MF, Siegmund B, et al. Mechanisms of molecular resistance and predictors of response to biological therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(11):790–802.

- Panaccione R, Feagan BG, Afzali A, et al. Efficacy and safety of intravenous induction and subcutaneous maintenance therapy with guselkumab for patients with Crohn’s disease (GALAXI-2 and GALAXI-3): 48-week results from two phase 3, randomised, placebo and active comparator-controlled, double-blind, triple-dummy trials. Lancet. 2025;406(10501):358–75.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Chapman JC, Colombel JF, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(3):213–23.

- Jairath V, Acosta Felquer ML, et al. IL-23 inhibition for chronic inflammatory disease. Lancet. 2024;404(10463):1679–92.

- Loftus EV Jr, Colombel JF, Takeuchi K, et al. Upadacitinib therapy reduces ulcerative colitis symptoms as early as day 1 of induction treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(9):2347–58.e6.

- Danese S, Vermeire S, Zhou W, et al. Upadacitinib as induction and maintenance therapy for moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: results from three phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, randomised trials. Lancet. 2022;399(10341):2113–28.

- Loftus EV Jr, Panés J, Lacerda AP, et al. Upadacitinib induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2023;388(21):1966–80.

- Damianos JA, Osikoya O, Brennan G. Upadacitinib for acute severe ulcerative colitis: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025;31(4):1145–9.

- Sandborn WJ, D’Haens G, Wolf DC, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet. 2023;401(10383):1159–71.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dubinsky MC, Sands BE, et al. Efficacy and safety of etrasimod in patients with moderately to severely active isolated proctitis: results from the phase 3 ELEVATE UC clinical programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(8):1270–82.

- Ahuja D, Luo J, Qi Y, et al. Impact of treatment response on risk of serious infections in patients with Crohn’s disease: secondary analysis of the PYRAMID Registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22(6):1286–94.e4.

- Solitano V, Ahuja D, Lee HH, et al. Comparative safety of JAK inhibitors vs TNF antagonists in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(9):e2531204.

- Sands BE, Afzali A, Irving PM, et al. Ustekinumab versus adalimumab for induction and maintenance therapy in biologic-naive patients with moderately to severely active Crohn’s disease: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, phase 3b trial. Lancet. 2022;399(10342):2200–11.

- Ferrante M, D’Haens G, Jairath V, et al. Efficacy and safety of mirikizumab in patients with moderately-to-severely active Crohn’s disease: a phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and active-controlled, treat-through study. Lancet. 2024;404(10470):2423–36.

- Barberio B, Gracie DJ, Black CJ, et al. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in induction and maintenance of remission in luminal Crohn’s disease: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2023;72(2):264–74.

- Vuyyuru SK, Nguyen TM, Murad MH, et al. Comparative efficacy of advanced therapies for achieving endoscopic outcomes in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22(6):1190–99.e15.

- Kapizioni C, Desoki R, Lam D, et al. Biologic therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: real-world comparative effectiveness and impact of drug sequencing in 13,222 patients within the UK IBD BioResource. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(6):790–800.

- Gisbert JP, Marín AC, McNicholl AG, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the efficacy of a second anti-TNF in patients with inflammatory bowel disease whose previous anti-TNF treatment has failed. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(7):613–23.

- Shehab M, Alrashed F, Alsayegh A, et al. Comparative efficacy of biologics and small molecule in ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;23(2):250–62.

- Solitano V, Facciorusso A, Jess T, et al. Comparative risk of serious infections with biologic agents and oral small molecules in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21(4):907–21.e2.

- Sands BE, Kozarek R, Spainhour J, et al. Safety and tolerability of concurrent natalizumab treatment for patients with Crohn’s disease not in remission while receiving infliximab. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(1):2–11.

- Feagan BG, Sands BE, Sandborn WJ, et al. Guselkumab plus golimumab combination therapy versus guselkumab or golimumab monotherapy in patients with ulcerative colitis (VEGA): a randomised, double-blind, controlled, phase 2, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8(4):307–20.

- Solitano V, Ogunsakin RE, Yuan Y, et al. Effectiveness and safety of advanced combination treatment in patients with refractory inflammatory bowel disease or concomitant immune-mediated disease or extraintestinal manifestations: a multicenter Canadian study. Am J Gastroenterol. Online ahead of print. doi:10.14309/ajg.0000000000003573C

- Solitano V, Ma C, Hanžel J, Panaccione R, Feagan BG, Jairath V. Advanced combination treatment with biologic agents and novel small molecule drugs for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2023;19(5):251–63.

Editor-in-Chief

John K. Marshall, MD MSc FRCPC CAGF AGAF

Professor, Department of Medicine

Director, Division of Gastroenterology

McMaster University

Hamilton, ON

Contributing Author

Vipul Jairath, MBChB DPhil FRCP FRCPC

Professor of Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology

Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry

Western University

London, ON

Mentoring in IBD Curriculum Steering Committee

Alain Bitton, MD FRCPC, McGill University, Montreal, QC

Karen I. Kroeker, MD MSc FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Cynthia Seow, MBBS (Hons) MSc FRACP, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Jennifer Stretton, ACNP MN BScN, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON

Eytan Wine, MD PhD FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

IBD Dialogue 2026·Volume 22 is made possible by unrestricted educational grants from…

![]()

![]()

Published by Kalendar Inc., 7 Haddon Avenue, Scarboro, ON M1N 2K7

© Kalendar Inc. 2026. All rights reserved. None of the contents may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the sponsors, the grantor, or the publisher.