IBD in the Elderly

IBD in the Elderly

May 28, 2024

Introduction

The objectives of this presentation were to examine current and future therapies for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with a focus on their safety and efficacy in elderly patients.

In 2023, Crohn’s and Colitis Canada published their “Impact of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Canada” report, that contained a specific section on IBD in seniors. It highlighted that one out of every 88 elderly individuals in Canada have IBD. The prevalence is increasing by 2.76% per year due both to more elderly individuals being diagnosed and aging of the existing IBD population. Furthermore, 15% of all persons newly diagnosed with IBD are >65 years of age.1

IBD in the Elderly: What makes it different?

The elderly IBD population has complex medical needs and faces unique barriers to care. Specifically, they are more commonly on polypharmacy, have more comorbidities, and have increased risk of shingles, pneumonia, postoperative complications, cognitive impairment, and cancer. With their increased likelihood of being on multiple medications, there is a greater frequency of drug-drug interactions and drug-related side effects. In terms of barriers to care, the elderly patient may have mobility restrictions, logistic challenges, and frailty.1

Access to care and information

In patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis (UC) >60 years of age, there is a higher rate of treatment failure compared with younger adults (28.4% vs. 12.2%). There is no difference in patients older vs. younger than 60 years of age with respect to adverse disease-related outcomes (hospitalizations, surgery, treatment escalation). However, elderly-onset UC is associated with other increased risks: a 3-fold of cytomegalovirus (CMV); a 2.4-fold of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), and a 3-fold of all cancers.1

Comparative efficacy

Accessing IBD care continues to be a challenge in Canada, and this is of particular concern for elderly patients. A population-based cohort study in Ontario assessed health service utilization in patients with elderly-onset IBD and found that when a gastroenterologist is involved in care, there are improved outcomes, such as less surgery and more frequent use of biologics.2 A study that assessed rural and urban disparities in the care of Canadians with IBD showed that rural patients were less likely to receive IBD care from a gastroenterologist, and this difference was most pronounced among patients >65 years of age (33% vs. 59.2%, p<0.0001).3

While virtual care becomes increasingly common in managing IBD, it may be difficult for older individuals to access IBD care through online applications due to reduced technological literacy. Specifically, a study using an IBD-specific electronic medical record system found that the self-reported mean information technology literacy scores worsen with advancing age,4 thus it is important to think about how to optimally communicate with elderly patients.

Comorbidities in Elderly Patients with IBD

A Canadian study showed an increased risk of multiple comorbidities in the general IBD population including cardiac disease (hazard ratio [HR]=1.24), cerebrovascular disease (HR=1.19), peripheral vascular disease (HR=1.36), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (HR=1.38), cancer (HR=1.21), and type 2 diabetes (HR=1.17). Many of these comorbidities are even more common in elderly patients.5

In addition, recent studies with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have provided substantial insight on vaccine response in elderly individuals. Studies have consistently demonstrated that elderly patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases have suboptimal response to vaccination.6-8

Treatment of Elderly Patients with IBD9

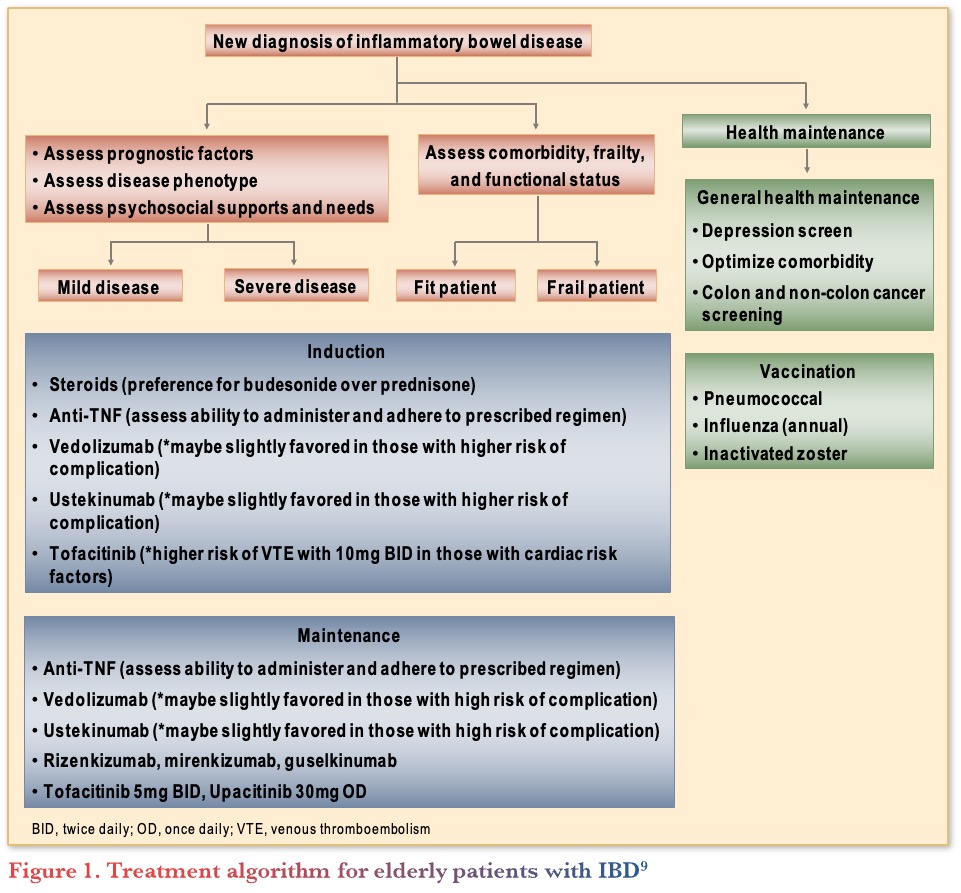

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) published clinical guidelines on the management of IBD in elderly patients.9 They included guidance on how to manage elderly patients with symptoms suggestive of IBD. Following a new diagnosis of IBD in elderly patients, the next steps are to assess prognostic factors, disease phenotype, psychosocial support, comorbidity, frailty, and function (see Figure 1). Dr. Bernstein noted that it is important to spend extra time in discussion with elderly patients, with multidisciplinary support, if possible, to fully assess their needs.

Biologics

A pooled analysis of data from randomized trials with anti-TNFs in UC reported no significant differences in efficacy of anti-tumour necrosis factor agents (TNFs) for either inducing or maintaining remission in older (>60 years of age) vs. younger (<60 years of age) patients. Safety data showed higher rates of serious adverse events (AEs) and hospitalizations compared to younger patients, but similar rates of severe and non-severe infections. A logistic regression analysis showed that age was a more significant predictor of the AE profile than medications.10

The PYRAMID Registry analyzed treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) on anti-TNFs for IBD based on age and found a significantly higher rate of severe AEs, any infections, serious infections, AEs leading to discontinuation, AEs leading to deaths, and deaths including non-treatment emergent deaths in patients ≥60 years compared to younger patients.11

Newer biologics with improved safety profiles have become their “go to” option in elderly patients for many gastroenterologists. For example, vedolizumab is a common first-line option for elderly patients with IBD, but it is important to still be aware of the limited data in this patient population. Specifically, registration trials for vedolizumab in UC (GEMINI 1) and Crohn’s disease (CD; GEMINI 2) included a very small number of patients ≥65 years of age (4% UC, 2% CD). A post hoc analysis investigated the efficacy and safety stratified by age and found that for UC, clinical response at week 6 and clinical remission at week 52 were not quite significantly superior to placebo in elderly patients, and similar results were seen in CD.12

In addition, the IG-IBD LIVE study looked at real-world effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in elderly (n=198) vs. matched non-elderly (n=396) patients. The results showed that non-elderly patients with UC had a significantly higher persistence on vedolizumab compared to elderly patients (67.6% vs. 51.4%, p=0.02). The study identified age as the only predictor of non-persistence in patients ≥65 years of age in UC, but in CD predictors included a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) >2, previous anti-TNF use, concomitant steroid use, and moderate-severe vs. mild disease. In terms of effectiveness, age >65 years did not seem to affect vedolizumab efficacy (clinical and endoscopic remission at 24 weeks) in CD, but age was associated with a lower likelihood of achieving clinical and endoscopic remission at 24 weeks in UC.13

Interestingly, a retrospective study of individuals >60 years treated with either anti-TNF or vedolizumab found that more individuals with CD (but not UC) on anti-TNF were in clinical remission at three months, while there was no significant difference between the treatments in at 6- and 12-months in UC or CD. Furthermore, infection rates were similar (20% anti-TNF; 17% vedolizumab, p=0.54).14

For the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, real-world evidence from the ENEIDA Registry from Spain showed similar effectiveness, treatment persistence, and safety results in patients older or younger than 60 years of age.15

For IL-23 inhibitors, post-hoc analysis of the Phase 3 studies of risankizumab in CD included 32 patients ≥65 of age (5.9%) and found that induction and maintenance treatment was well tolerated across age groups.16 Mirikizumab subgroup analysis from the phase 3 study (LUCENT-1) showed no difference in rates of clinical remission at week 12 in patients older or younger than 65 years of age.17

JAK inhibitors

Analysis of data from the tofacitinib UC clinical program stratified by age showed that age did not impact treatment response with respect to endoscopic and clinical outcomes at weeks 8 and 52, albeit based on a small number of patients. However, patients ≥65 years of age had higher rates of discontinuation due to AEs and herpes zoster (HZ),18 speaking to the need to vaccinate patients regardless of their age.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the prevalence of IBD amongst the elderly will continue to grow. Thus far, studies have largely “missed the boat” on including older patients and there remains an unmet need for clinical trial data to help guide management of this important demographic.

Clinical Case

- Henry—72-year-old retired geologist

- History of left-sided colitis for 8 years

- Initially treated with tapering course of corticosteroids

- Maintained on 5-ASA 4.8 g daily

- Past medical history remarkable for myocardial infarction 3 years ago, requiring 2 stents

- Echo last year shows ejection fraction of 45%

- Four months ago:

- He received antibiotics for dental infection

- Developed C. difficile infection

- Successfully treated with vancomycin

- Since then:

- Flaring (6 BM/day, 50% with blood)

- Afraid to go golfing due to fear of accidents

- Compliant with 5-ASA

- Treated with budesonide-MMX with limited benefit

- Colonoscopy shows Mayo 1-2 left-sided colitis

Commentary

- The majority of gastroenterologists would choose to start vedolizumab in this case.

- Undertreatment a bigger issue than overtreatment in elderly patients.

Case Evolution

- You recommend vedolizumab

- Henry agrees

- He receives 3 induction doses followed by 300 mg every 8 weeks

- Six months later, he is doing well:

- 1–2 formed stools daily without blood or urgency

- FCP 52

- Oral 5-ASA is discontinued

- He subsequently complains of inflammatory-type joint pain with morning stiffness

- You add methotrexate, but this causes nausea and is discontinued

- Flex sigmoidoscopy shows no active colitis, only chronic changes

Commentary

- Refer Henry to a Rheumatologist.

- Given the higher frequency of comorbidities in elderly patients, it is important to coordinate care with other specialists.

- Investigate the joint symptoms more and rule out osteoarthritis given his colitis was under control.

Case Evolution

- You refer to rheumatology

- Decide to add sulfasalazine while you wait

- He does not tolerate sulfasalazine and it is discontinued

- He sees rheumatologist 3 months later

- Recommends that you switch to either an anti-TNF or JAK inhibitor

Commentary

- Most gastroenterologists would switch to an anti-TNF, as many elderly patients did well when anti-TNF was the only option.

Case Evolution

- You assess Henry in clinic and discuss treatment options

- He is interested in oral medication that rheumatologist mentioned as he thinks this would fit best with his lifestyle

- You provide information about upadacitinib and arrange for recombinant zoster vaccine prior to starting

- Henry calls your office the following week

- He has read a black box warning for JAK inhibitors for individuals >50 years of age with cardiac risk factors

- He reminds you of the heart attack he had several years ago

Commentary

- Most gastroenterologists would stick with an anti-TNF in this case, as the ORAL Surveillance study has left a legacy of fear round JAKi, particularly in elderly patients, even if unfounded.

Case Evolution

- He decides on anti-TNF therapy (infliximab).

Commentary

- Gastroenterologists recommend Henry obtain the recombinant zoster and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccines.

- They would stop the vedolizumab after his first infliximab infusion.

References

-

-

- Shaffer SR, Kuenzig ME, Windsor JW, et al. 2023 Impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: Special populations-IBD in seniors. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023;6(Suppl 2):S45–54.

- Kuenzig ME, Stukel TA, Kaplan GG, et al. Variation in care of patients with elderly-onset inflammatory bowel disease in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2021;4:e16–30.

- Benchimol EI, Kuenzig ME, Bernstein CN, et al. Rural and urban disparities in the care of Canadian patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:1613–26.

- Kaazan P, Li T, Seow W, et al. Assessing effectiveness and patient perceptions of a novel electronic medical record for the management of inflammatory bowel disease. JGH Open. 2021;5:1063–70.

- Bernstein CN, Nugent Z, Shaffer S, et al. Comorbidity before and after a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:637–51.

- Al-Janabi A, Littlewood Z, Griffiths CEM, et al. Antibody responses to single-dose SARSCoV-2 vaccination in patients receiving immunomodulators for immune-mediated inflammatory disease. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:646–48.

- Kennedy NA, Lin S, Goodhand JR, et al. Infliximab is associated with attenuated immunogenicity to BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with IBD. Gut. 2021;70:1884–93.

- Kappelman MD, Weaver KN, Zhang X, et al. Factors affecting initial humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccines among patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:462–9.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Nguyen GC, Bernstein CN. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Elderly Patients: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:445–51.

- Cheng D, Cushing KC, Cai T, et al. Safety and efficacy of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in older patients with ulcerative colitis: Patient-level pooled analysis of data from randomized trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:939–46.e4.

- Colombel J-F, D’Haens G, Reinisch W, et al. PYRAMID Registry: Long-term safety of adalimumab by age in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S396–7.

- Yaznick V, Khan, N, Dubinsky M, et al. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease patients stratified by age. Adv Ther. 2017;34:542–59.

- Pugliese D, Privitera G, Crispino F, et a. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in a matched cohort of elderly and nonelderly parients with inflammatory bowel disease: The IG-IBD LIVE study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56:95–109.

- Adar T, Faleck D, Sasidharan S, et al. Comparative safety and effectiveness of tumor necrosis factor α antagonists and vedolizumab in elderly IBD patients: A multicentre study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:873–9.

- Casas-Deza D, Lamuela-Calvo LJ, Gomollón F, et al. Effectiveness and safety of ustekinumab in elderly patients with Crohn’s disease: Real World Evidence from the ENEIDA Registry. J Crohn’s Colitis 2023;17:83–91.

- Colombel J-F, Danese S, Martin N, et al. Safety profile of risankizumab in Crohn’s disease patients by age: Post-hoc analysis of the phase 3 ADVANCE, MOTIVATE, and FORTIFY studies. DDW 2023; Tu1717.

- D’Haens G, Dubinsky M, Kobayashi T, et al. Mirikizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2022;388(26):2444–55.

- Lichtenstein GR, Bressler B, Francisconi C, et al. Assessment of safety and efficacy of tofacitinib, stratified by age, in patients from the ulcerative colitis clinical program. Inflamm Bowel Dis J. 2023;29:27–41.

-

Editor-in-Chief

John K. Marshall, MD MSc FRCPC CAGF AGAF

Professor, Department of Medicine

Director, Division of Gastroenterology

McMaster University

Hamilton, ON

Contributing Author

Charles N. Bernstein, MD FRCPC

Distinguished Professor of Medicine

Director, University of Manitoba IBD Clinical and Research Centre

Bingham Chair in Gastroenterology

Winnipeg, MB

Mentoring in IBD Curriculum Steering Committee

Alain Bitton, MD FRCPC, McGill University, Montreal, QC

Karen I. Kroeker, MD MSc FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Cynthia Seow, MBBS (Hons) MSc FRACP, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Jennifer Stretton, ACNP MN BScN, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON

Eytan Wine, MD PhD FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

IBD Dialogue 2024·Volume 20 is made possible by unrestricted educational grants from…

![]()

![]()

Published by Catrile & Associates Ltd., 167 Floyd Avenue, East York, ON M4J 2H9

(c) Catrile & Associates Ltd., 2023. All rights reserved. None of the contents may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the sponsors, the grantor, or the publisher.