Positioning Advanced Therapies for Ulcerative Colitis

Positioning Advanced Therapies for Ulcerative Colitis

February 27, 2024

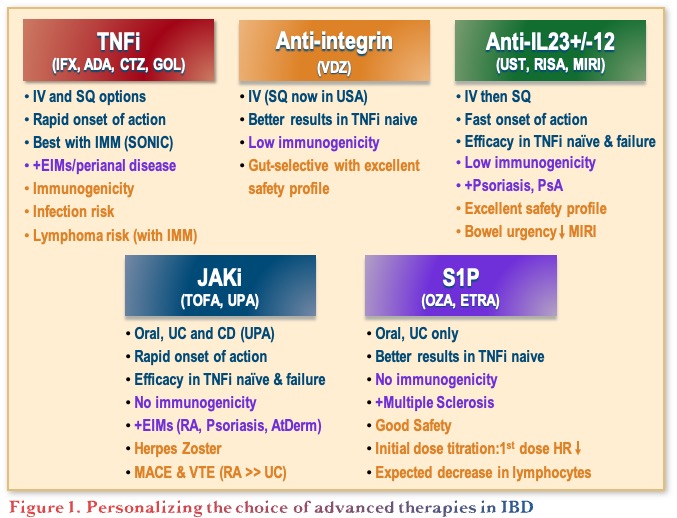

Introduction: Current and Emerging Therapies for IBD

The objectives of this presentation were to discuss current and imminent therapies, both first line and second line, and consider how to personalize the therapeutic approach in ulcerative colitis (UC). There are many options currently available for UC, now including anti-tumour necrosis factor (anti-TNFs), anti-integrins, anti-interleukins (i.e. the anti-IL-12/23 and anti-IL-23 agents), Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor (S1PR) modulators.1 The recent introduction of non-biologic small molecules (e.g., JAK inhibitors and S1PR modulators) have added to the treatment landscape, providing the benefits of oral administration, a short half-life, rapid clearance, and lack of immunogenicity.2,3 This evolution of choice has led to the challenge of personalizing the choice of advanced therapy by taking into consideration efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety considerations, which differ between the classes, as outlined in Figure 1.

Treatment Sequencing in UC

Along with the increasing number of therapeutic options in UC, the treatment goals continue to evolve, moving from clinical remission to biologic remission, to endoscopic remission, and more recently to consider histologic remission.4,5 Dr. Regueiro noted that histologic endpoints are currently used as a treatment guide rather than to inform treatment changes. That is, treatment would not be changed for a patient who has improved symptomatically and is endoscopically normal, but still has histologic inflammation.

In practice, treatment selection in UC is mainly driven by assessment of the patient’s risk for complicated disease and colectomy. Specifically, patients considered at low risk for colectomy receive 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and limited steroids if needed, while patients considered at high risk for colectomy receive early advanced therapies.6 Risk factors for complicated disease indicating the need for early advanced therapy include age <40 years, extensive colitis, deep ulcers, corticosteroid dependency, a history of hospitalization, high C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), Clostridium difficile infection, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.6

Head-to-Head Studies

With respect to data to guide sequencing of UC therapies, there is only one head-to-head study in UC at the time of this publication, the VARSITY study, a randomized, controlled trial of vedolizumab vs. adalimumab in patients with active UC.7 The results showed vedolizumab to be significantly superior to adalimumab with respect to clinical remission and mucosal healing endpoints. However, the study was limited by the lack of dose escalation, and information on drug levels, and for patients on steroids or immunomodulators, there was no difference observed between groups.7

Network Meta-analyses

Given the lack of comparative studies, network meta-analyses (NMAs) are relied upon to gain further insight, despite their limitations. There are several NMAs with similar results, and these will continue to be updated. For example, a systematic review with NMA on first‐line induction pharmacotherapy for moderate to severe UC found the largest effect size for vedolizumab and infliximab.8

Another NMA in moderate to severe UC, analyzed clinical remission results from 28 trials (12,504 patients) and found that upadacitinib and infliximab ranked first for efficacy. With respect to endoscopic improvement, data were analyzed from 27 trials (11,733 patients) and ranked upadacitinib and infliximab highest for efficacy, with upadacitinib 45 mg identified as superior in anti-TNF-exposed patients.9 With respect to adverse events (AEs), no drug was more likely than placebo to lead to serious AEs (SAEs) and the risk of SAEs was significantly less with vedolizumab and golimumab than with placebo. Upadacitinib 45 mg was the most likely to lead to AEs, and tofacitinib 10 mg bid ranked last for infections (significant compared to placebo).9

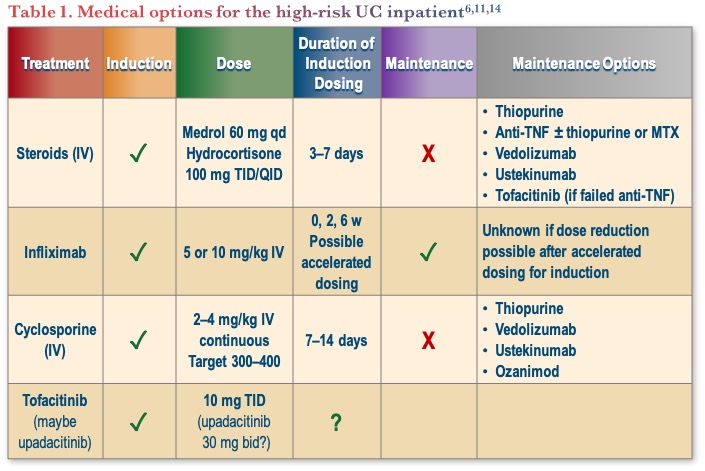

Acute Severe Ulcerative Colitis (ASUC)

A clinical challenge is choosing therapy for patients with ASUC that are failing intravenous (IV) corticosteroids, with relevant considerations listed in Table 1. Cyclosporine and infliximab have shown similar efficacy with no difference in long-term colectomy-free survival.10 The question remains as to where JAK inhibitors stand in terms of maintenance, as tofacitinib has limited data showing efficacy in the short-term, but there are no data on avoidance of colectomy as of yet.11-13

Dr. Regueiro shared his treatment approach for ASUC, which includes the use of IV steroids for 1–2 days. If no response, he considers IV cyclosporin, IV infliximab (accelerated dosing), or a JAK inhibitor, and if they still do not respond, he would move to colectomy. He emphasized that colectomy is not a failure, as the goal is to save the patient’s life, not their colon. A key point for the treatment of ASUC is the need to act quickly.

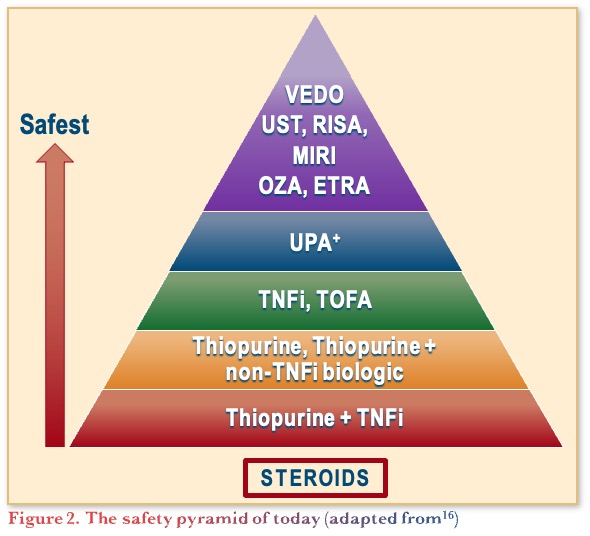

Safety Considerations for Positioning Therapies for UC

The safety pyramid of therapies in UC, shown in Figure 2, is primarily based on clinical experience and opinion. It has evolved since the original version published in 2019,15 to the most recent adapted version published in November 2023.16 It is important to highlight that surgery is sometimes the best option, and that inadequate treatment is an adverse event.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Dr. Regueiro summarized that there is still a lack of data on how to best position therapy and, as such, approaches are adapted based on experience. He summarized how he positions treatment in UC taking into account all the factors discussed. Specifically, he chooses infliximab with azathioprine as first choice for ASUC, with upadacitinib as his second-line choice based on evolving data. For the moderate UC outpatient, there are several reasonable options including vedolizumab, ustekinumab, mirikizumab, or anti-TNF. For anti-TNF failures, he would choose upadacitinib and prefers to use S1PR modulators for patients on the milder end of the moderate disease stratum. The presence of extraintestinal manifestations and concomitant immune-mediated inflammatory disorders also impacts the choice, depending on whether they are driven by bowel inflammation. Lastly, for patients considering pregnancy, he continues monoclonal antibodies throughout pregnancy, but stops small molecule therapy one month prior to conception.

Clinical Case

- Erica—an otherwise healthy 27-year-old lawyer with longstanding left-sided ulcerative colitis

- On oral 5-ASA 4.8 g per day

- Previous flare 4 years prior

- You see her in your office because:

- 6-week history of 5 to 6 loose stools per day

- Mostly bloody associated with abdominal cramps

- 10 lb weight loss

- No history of antibiotic use or recent travel

- Tests done week before by family practitioner reveal:

- CBC-Hb 109 g/l

- Platelets 550

- CRP 15 mg/l

- Fecal calprotectin >2100 mcg/g

- Stool C. difficile and C&S negative

- You discuss therapeutic options including a course of oral corticosteroids

- She has taken prednisone in the past and asks if there are any other options

Commentary

- In this case, gastroenterologists would consider the use of vedolizumab (IV for induction and IV or subcutaneous [SC] for maintenance) followed by an anti-TNF (many prefer adalimumab because of SC administration, but any of the anti-TNFs would be appropriate).

- Many gastroenterologists would include JAK inhibitors in the discussion as an option.

- When discussing JAK inhibitors, they speak to the fact that the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) was from the Oral Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial (ORAL) Surveillance study, therefore it is not clear if that translates to the IBD population. Furthermore, in IBD studies with tofacitinib and upadacitinib, long-term data collected to date has not shown a higher risk. Until there are more data, it may be reasonable to avoid JAKi in patients over the age of 65 who have cardiovascular risk.

Case Evolution

- After discussion, you initiate oral prednisone 40 mg /day

- Colonoscopy shows Mayo 2 colitis extending from the rectum to proximal transverse colon

- Biopsies show active chronic colitis

- No dysplasia

- She returns to your office 2 weeks later

- Complains of sleep disturbance and minimal improvement despite oral steroid

- Now has 4 loose stools/day, mostly bloody, some cramps

- You discuss various therapeutic options and mention the need to escalate to advanced therapies

- Erica has seen TV commercials on various US channels about these agents

- She is concerned about:

- Risks of infections

- Cancer

- Potential impact on future pregnancy

Commentary

- At this point, most gastroenterologists would revisit the discussion around the use of vedolizumab or anti-TNF.

- Pre-screening tests including basic bloodwork, and tests for hepatitis and tuberculosis (skin or QuantiFERON depending on the province), are completed regardless of the molecule being initiated, to leave the option open for future switching.

- There remains hesitation to use a JAK inhibitor in this case due to the potential for pregnancy, however given the short half-life, it depends on how soon the patient is planning for pregnancy.

Case Evolution

- After discussion, you jointly decide on vedolizumab

- She receives a 3-dose induction and a maintenance regimen every 8 weeks

- Prednisone is tapered and discontinued over a 2-month period

- You see her 6 months later

- After feeling much better, she now has a recurrence of low-grade symptoms:

- Abdominal cramps

- 3 to 4 soft stools/day, half are bloody with mucus

- Vedolizumab is increased to every 4 weeks

- She remains symptomatic after 3 months

- Fecal calprotectin elevated >2100

- She asks about other therapeutic options

- Shares her preference for an oral medication

Commentary

- Given this patient has failed vedolizumab and has moderate disease, many gastroenterologists would choose to switch to infliximab and consider combination therapy with azathioprine, removing it once deep remission is achieved.

- However, some gastroenterologists have concerns with sustainability of response to anti-TNFs, so would instead choose an IL-12/23 or IL-23 inhibitor.

- The recent phase 3 SEQUENCE head-to-head trial found risankizumab to be superior to ustekinumab in CD.17 There are no similar head-to-head data yet available in UC. A limitation of the study was that ustekinumab was used at the q8w dose while in Canada, many gastroenterologists use q4w. However, there is no data demonstrating that q4w is superior to q8w dosing.

- With respect to deciding to switch or add a treatment:

- Consider adding an agent if the patient has experienced a benefit but has not quite achieved the targeted level of remission.

- In contrast, if the agent was not providing benefit, switch out of class, as combination therapy is likely to be most advantageous if used upfront.

- Some combination therapies with 2 mechanisms of action have shown a signal towards higher remission, but this is not precision medicine, rather a “hammer and nail” approach.

- Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is mainly used for anti-TNFs, as there is a lack of understanding on target levels for other agents.

- Aside from that, testing for the presence or absence of drug can be helpful regardless of the therapy, though many would dose optimize without TDM.

Case Evolution

- After discussion, ustekinumab is initiated

- Within one month symptoms resolved

- She remains on maintenance therapy every 8 weeks

- Subsequently undergoes a surveillance colonoscopy, which shows endoscopic remission (Mayo 0)

- Surveillance biopsies throughout the colon show:

- No dysplasia but,

- Several areas with mild active chronic colitis with or without basal plasmacytosis

- She sees you in follow-up and asks to stop the ustekinumab because she wishes to get pregnant

Commentary

- For next steps in this case, generally gastroenterologists do not de-escalate therapy.

- Upadacitinib is often chosen first line for sicker patients, then once they achieve remission, they are switched to an IL-23 inhibitor or vedolizumab. This approach can also be used in patients that want to become pregnant. In this patient’s case, given her prior lack of response to vedolizumab, most would favor an IL-23 inhibitor.

- There is concern around changing treatment in patients that have partially responded to a therapy; “Don’t let perfect be the enemy of good”. As such, if a patient is doing well and has good endoscopic and biochemical response, treatment is continued, and the patient is monitored more frequently.

- With respect to stop rules for biologics, there is no data on this, so the main message to patients is to continue treatment.

- A failure to achieve histological outcomes is not used as a basis for treatment adjustments

- It is important to speak to the pathologists to better understand what histological changes mean, as histological results can be used as an explanation on why not to stop therapy.

References

- Fukuda T, Naganuma M, Kanai T. Current new challenges in the management of ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. 2019;17:36–44.

- Hemperly A, Sandborn WJ, Vande Casteele N. Clinical pharmacology in adult and pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2527–42.

- Coskun M, Vermeire S, Nielsen OH. Novel Targeted Therapies for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2017;38(2):127–42.

- Rogler G, Vavircka S, Schoepfer A, Lakatos PL. Mucosal healing and deep remission: what does it mean? World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(43):7552–60.

- Walsh AJ et al. Current best practice for disease activity assessment in IBD. Nature Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:567–79.

- Dassopoulos T, Scherl, E, Schwartz R, et al. Ulcerative colitis care pathway. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:238–45.

- Sands BE, Peryin-Biroulet L, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Vedolizumab versus adalimumab for moderate-to-severe ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1215–26.

- Singh S, Fumery M, Sandborn WJ, Murad MH. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: first- and second-line pharmacotherapy for moderate-severe ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(2):162–75.

- Burr NE, Cracie DJ, Black CJ, Ford AC. Efficacy of biological therapies and small molecules in moderate to severe ulcerative colitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut. 2021;71(10):1976–87.

- Laharie D, Bourreille A, Branche J, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with steroid-refractory acute severe UC treated with ciclosporin or infliximab. Gut. 2018; 67(2):237–43.

- Berinstein JA, Sheehan J, Dias M, et al. Tofacitinib for biologic-experienced hospitalized patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis: A retrospective case-control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19(10):2112–20.e1.

- Berinstein JA, Steiner CA, Regal RE. Efficacy of induction therapy with high-intensity tofacitinib in 4 patients with acute severe ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019; 17(5):988–90.e.1.

- Kotwani P, Terdiman J, Lewin S. Tofacitinib for rescue therapy in acute severe ulcerative colitis: A real-world experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:1026–28.

- Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AH, Siegel CA, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(3):384–413.

- Queiroz NS, Regueiro M. Safety considerations with biologics and new inflammatory bowel disease therapies. Curr Opinion Gastroenterol. 2020;36(4):257–264.

- Bhat S, Click B, Regueiro M. Safety and Monitoring of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Advanced Therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023; epub ahead of print: https://doi.org/10.1093/ibd/izad120

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Chapman JC, Colombel J-F. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease: results from the phase 3b SEQUENCE study. UEGW 2023; Abstract LB01.

Editor-in-Chief

John K. Marshall, MD MSc FRCPC CAGF AGAF

Professor, Department of Medicine

Director, Division of Gastroenterology

McMaster University

Hamilton, ON

Contributing Author

Ashwin Ananthakrishnan, MD MPH,

Associate Professor of Medicine,

Division of Gastroenterology,

Massachusetts General Hospital & Harvard Medical School,

Boston, MA, USA

Mentoring in IBD Curriculum Steering Committee

Alain Bitton, MD FRCPC, McGill University, Montreal, QC

Karen I. Kroeker, MD MSc FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Cynthia Seow, MBBS (Hons) MSc FRACP, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Jennifer Stretton, ACNP MN BScN, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON

Eytan Wine, MD PhD FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

IBD Dialogue 2024·Volume 20 is made possible by unrestricted educational grants from…

![]()

![]()

Published by Catrile & Associates Ltd., 167 Floyd Avenue, East York, ON M4J 2H9

(c) Catrile & Associates Ltd., 2023. All rights reserved. None of the contents may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the sponsors, the grantor, or the publisher.