Pouchitis

Pouchitis

March 26, 2024

Introduction

The objectives of this presentation were to examine how to diagnose pouch disorders, explore how to manage acute and chronic pouchitis, and discuss when to refer to a surgeon. A recent review suggests pouchitis is common, with a cumulative probability of 20% at 1 year after pouch formation and up to 40% at 5 years.1 Meanwhile, data from the UK ileoanal pouch registry speak to the importance of optimizing surgical outcomes in an effort to ‘get it right from the start’. The registry included 5352 patients from 2012–17 and found a complication rate of 23% and a failure rate of 5%. Remarkably, the average number of ileal pouch-anal anastomoses (IPAA) performed per surgeon was 3 per year, and 25% of surgeons had performed just 1 IPAA in the last 5 years. These low volume surgeons had higher rates of complications and failures underscoring the importance of referring patients to surgeons with appropriate experience and clinical volume.2

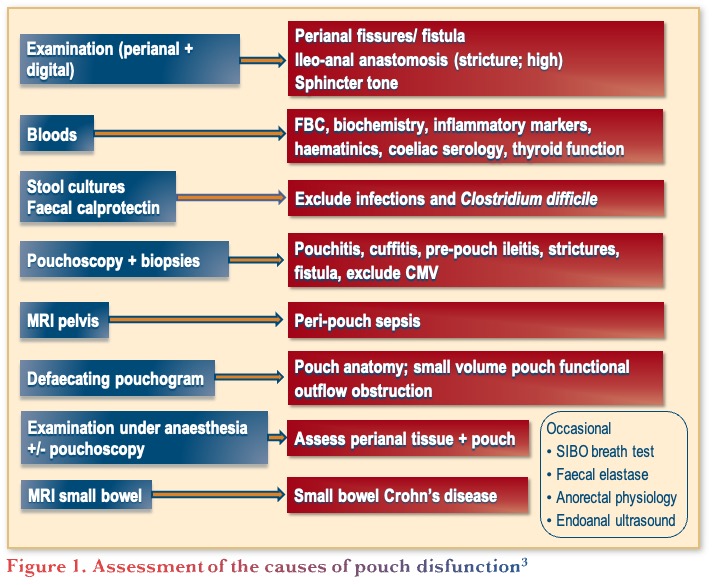

Assessment of the causes of pouch dysfunction

Pouch dysfunction can be due to many reasons beyond pouchitis such as, inflammatory causes (e.g., Crohn’s disease), mechanical causes (e.g., small reservoir), functional causes (e.g., evacuation disorder), or other causes (e.g. bacterial overgrowth).3 Therefore, it is important to carefully assess the cause of pouch dysfunction, taking into consideration the initial indication for surgery, type of pouch and anastomosis, histopathology of the colectomy specimen, presence of extra-intestinal manifestations, history of bowel symptoms, previous pouch function and symptoms, potential GI infection, and current medications.3 Given the range of causes, assessment of pouch dysfunction can involve many types of assessments, as illustrated in Figure 1, including physical examination, blood and stool tests, pouchoscopy, etc., noting that some of these assessments are only needed for specific clinical situations. A retrospective study on the management of patients with pouch dysfunction (n=121), found that the most frequent causes of pouchitis were anastomotic leakage (21%), primary idiopathic pouchitis (20%), and functional disorders (20%).4 However, identifying the cause can be challenging because symptoms, endoscopy, and histology often do not correlate, patients can present with multiple causes of pouchitis, and there is a lack of training in performing and reporting pouchoscopies.

Pouchitis assessment tools

The Pouch Disease Activity Index (PDAI) is an 18-point assessment tool that includes histologic, clinical, and endoscopic criteria, while the modified PDAI (mPDAI), is a shorter 12-point assessment, that excludes histology, while maintaining its diagnostic specificity and sensitivity.5 Recently, the Atlantic Pouchitis Index (API) was developed, which applies the Simple Endoscopic Score-Crohn’s Disease (SES-CD) to pouch endoscopy as a single segment. Data have shown that the correlation with the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was better using the SES-CD than the PDAI, however, the API excludes clinical symptoms.6,7

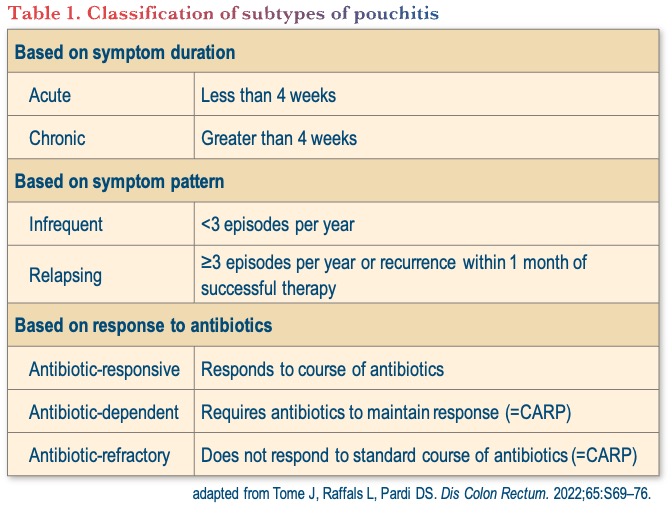

Classification of subtypes of pouchitis

The classification of subtypes of pouchitis is rather arbitrary and can be based on symptom duration, symptom pattern, and/or response to antibiotics, as shown in Table 1.

Management of pouchitis

Management of acute pouchitis

The European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) guidelines state that the majority of patients respond to metronidazole or ciprofloxacin, and that side effects are less frequent with ciprofloxacin monotherapy. Antidiarrheal drugs may be added to reduce the number of daily liquid stools. Similarly, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines recommend a 2-week course of ciprofloxacin or metronidazole, noting that ciprofloxacin is better tolerated and may be more effective than metronidazole.8,9

Management of chronic pouchitis

Around 60% of patients with acute pouchitis develop at least one recurrence and up to 19% develop chronic pouchitis that is refractory to antibiotics.10,11 There are 2 meta-analyses of biologics to treat chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis (CARP). One included 15 studies (311 patients) of which one was a randomized controlled trial. The pooled rate of clinical remission were 65.7%, 31%, and 47.4% with infliximab, adalimumab, and vedolizumab, respectively.12 The other meta-analysis included 26 studies (741 patients), with a variety of conditions pooled together (CARP/Crohn’s/cuffitis) and looked at clinical response as the endpoint. For the subgroup of patients with chronic pouchitis, it found clinical response rates of 51%, 47%, 41%, and 41% with infliximab, adalimumab, vedolizumab, and ustekinumab, respectively.13

The EARNEST trial was the first randomized controlled trial of advanced therapy in chronic pouchitis and investigated the use of intravenous vedolizumab in patients with active CARP after proctocolectomy and IPAA for ulcerative colitis (n=102). The results showed significant differences in favour of vedolizumab over placebo for mPDAI remission rate at week 14 (primary endpoint) and the key secondary efficacy endpoints of mPDAI remission at week 14, mPDAI response at weeks 14 and 34, and PDAI remission at weeks 14 and 34. Furthermore, the rate of sustained remission (remission at both weeks 14 and 34, mPDAI and PDAI) was significantly higher for vedolizumab versus placebo.14 Subsequent assessment of the endoscopic evaluations from 98 patients from the trial showed a greater reduction in ulcerated surface area with vedolizumab versus placebo at weeks 14 and 34, as well as higher rates of SES-CD remission (weeks 14 and 34) and mucosal healing (week 14).15

The evidence for other advanced therapies in the management of chronic pouchitis is limited and mainly anecdotal. Specifically, for Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi), there are data for tofacitinib from the GETAID TOFA-POUCH study group, which included 12 patients with CARP, of which 4 achieved steroid-free remission at 8 weeks.16 In addition, a case series from MSSM-Chicago of 14 patients with CARP, showed response to tofacitinib in 3 patients at 12 weeks.17 For ustekinumab, investigation is underway as the SOCRATES (Stelara fOr ChRonic AntibioTic rEfractory pouchitiS) study is recruiting subjects.18

Conclusions

In conclusion, Dr. Travis recapped that pouch dysfunction is not the same as pouchitis, therefore it is crucial to do a full assessment as to the cause(s). For acute pouchitis, the recommended first-line treatment is ciprofloxacin, with or without metronidazole, and vedolizumab is recommended for the treatment of chronic pouchitis. When treating patients with pouchitis, it is important to address the psychological burden and to apply a multidisciplinary approach when possible. For pouch dysfunction that is refractory to antibiotics and/or advanced therapies, ensure that all potential causes of pouch dysfunction have been considered and refer for help.

Clinical Case

- Mira—26-year-old non-smoking female

- Diagnosed with ulcerative colitis at age 9

- Initially treated with corticosteroids and 5-ASA

- Due to fulminant colitis, not responsive to intravenous corticosteroids and infliximab

- Underwent a restorative proctocolectomy with subsequent ileoanal pouch anastomosis surgery at age 15

- You first meet her at the pediatric to adult transition/young adult IBD clinic at age 18

- She recounts that:

- She usually has 7 semi-formed bowel movements a day

- No nocturnal wakening

- Occasionally has quite marked urgency and tenesmus in the absence of blood

- She admits she has been quite anxious about starting university and wonders if this may be contributing

- Stool cultures are negative for:

- Enteric pathogens

- C. difficile

Commentary

- In this case, most gastroenterologists would treat her

- with empiric antibiotics closely followed by rectal 5-ASA therapy.

- When possible, work with the surgeon, as they are most familiar with the pouch.

- Recent studies, as well as the EARNEST trial, have shown that FCAL >250 μg/g is the cut-off suggesting the need to treat with antibiotics.

Case Evolution

- Given her predominant symptoms of urgency and tenesmus, you prescribe 5-ASA suppositories for presumptive cuffitis

- She happily reports that symptoms returned to baseline after 4 weeks of daily suppositories

- You recommend she uses these on an as needed basis

- At annual follow up, she reports that over the last 2 months:

- Stool frequency increased to 10 BM/day

- 1 nocturnal BM

- Restarting rectal 5-ASA has not made a difference

- Repeat stool cultures are negative

- Pouchoscopy confirms acute pouchitis

- You prescribe 2 weeks of amoxiclav

- She does well for 6 months, but symptoms recur

- Her family physician prescribes another two courses of amoxiclav with only minor improvement in symptomatology

- Meanwhile, she is reminded not to use NSAIDs for sports-related injuries

- She requests a follow up appointment for recurrent abdominal pain associated with nausea, vomiting, urgency, tenesmus, and frequent bowel movements

Commentary

- At this point, most gastroenterologists would recommend repeat pouchoscopy.

- It was noted that it can be hard to differentiate Crohn’s disease of the pouch, but it is important to remember pre-pouch ileitis does not necessarily mean it is Crohn’s disease.

- Pouch anal anastomoses and strictures are common in these patients; thus, a digital rectum exam should be completed to ensure there is no stricture and redone every 2 years. There is also the opportunity to counsel patients on daily dilation.

Case Evolution

- Repeat pouchoscopy demonstrates:

- Erythema of the pouch

- Scattered ulcerations

- Some narrowing at and just above the pouch inlet

- You are only able to visualize the distal 3 cm of the pre-pouch ileum

- Worried about her nausea and vomiting, you arrange an MRE

- MRE confirms:

- Distal inflammation

- Also shows 10 cm segment of inflammation in the distal pre-pouch ileum

Commentary

- At this point in this case, gastroenterologists would initiate advanced therapy with vedolizumab, with some consideration for adalimumab.

- The EARNEST study was critical in informing treatment selection for these patients given the limited data in this patient population.

- Patients that are antibiotic dependent or require 3–4 courses/year should be on advanced therapy, as there is no longer a role for continuous antibiotic therapy.

- It was noted that access to a biologic may be limited for some patients based on diagnosis or reimbursement.

Case Evolution

- Mira does well on induction and maintenance vedolizumab therapy

- Congratulations! You had great foresight and should have co-authored the EARNEST trial!

- She required one dilatation of the pouch inlet a year after starting vedolizumab

- Subsequent, clinical, biochemical, radiologic, and endoscopic examinations confirm disease remission

- You see her in consultation a few years later in the IBD preconception clinic

- She continues to do well and is keen to start a family

Commentary

- In this case, gastroenterologist recommend delivery by C-section, due to concerns about stretch of the sphincter and subsequent impaired function.

- Successful vaginal delivery is possible, but in practice most patients value their pouch and want to protect it as much as possible.

References

- Outtier A, Ferrante M. Chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis: Management challenges. Clin Exper Gastroenterol. 2021:14;277–90.

- Association of Coloprotoctology of Great Britain and Ireland. Ileoanal Pouch Report 2017. Available at: https://www.acpgbi.org.uk/resources/224/ileoanal_pouch_report_2017

- Deputy M, Worley G, Patel K, et al. Long-term outcome and quality of life after continent ileostomy for ulcerative colitis: A systematic review. Colorectal Dis. 2021;23:1193–204.

- Ourô S, Thava B, Shaikh I, et al. Management of pouch dysfunction in a tertiary centre. Colorectal Dis. 2016;18:1167–71.

- Shen B, Achkar J-P, Connor JT, et al. Modified pouchitis disease activity index: a simplified approach to the diagnosis of pouchitis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:748–53.

- Samman MA, Shen B, Mosli MH, et al. Reliability among central readers in the evaluation of endoscopic disease activity in pouchitis. Gastrointest Endo. 2018;88:360–9.

- Sedano R, Ma C, Hogan M, et al. Development and validation of a novel composite index for the assessment of endoscopic and histologic disease activity in pouchitis: The Atlantic Pouchitis Index. DDW 2023 Abstract 352. Available at: https://ddw.digitellinc.com/live/8/page/56/1?eventSearchInput=sedano

- Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, et al. Third European evidence-based consensus on diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis. Part 1: definitions, diagnosis, extra-intestinal manifestations, pregnancy, cancer surveillance, surgery, and ileo-anal pouch disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–70.

- Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut. 2019;68:s1–106.

- Shen B, Lashner BA. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pouchitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;4:355–61.

- Madiba TE, Bartolo DC. Pouchitis following restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis: incidence and therapeutic outcome. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2001;46:334–37.

- Chandan S, Mohan B, Kumar A, et al. Safety and efficacy of biological therapy in chronic antibiotic refractory pouchitis: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:481–91.

- Shehab M, Alrashed F, Bessissow T. Biologic therapies for the treatment of post-ileal pouch anal anastomosis surgery chronic inflammatory disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Can Assoc Gastro. 2022;55:287–96.

- Travis S, Sliverberg MS, Danese S. Vedolizumab for the treatment of chronic pouchitis. N Eng J Med. 2023;388:1191–200.

- Jairath V, Feagan BG, Silverberg MS. Mucosal healing with vedolizumab in inflammatory bowel disease patients with chronic pouchitis: Evidence from EARNEST, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. ECCO 2023;OP08.

- Uzzan M, Nachury M, Ameiot A, et al. Effectiveness and safety of tofacitinib in patients with chronic pouchitis multirefractory to biologics. Dig Liver Dis. 2023;55(8):1158–60.

- Akiyama S, Cohen NA, Kayal M, et al. Treatment of chronic inflammatory pouch conditions with tofacitinib: A case series from 2 tertiary IBD centers in the United States. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29(9):1504–7.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Stelara fOr ChRonic AntibioTic rEfractory pouchitiS (SOCRATES). Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04089345

Editor-in-Chief

John K. Marshall, MD MSc FRCPC CAGF AGAF

Professor, Department of Medicine

Director, Division of Gastroenterology

McMaster University

Hamilton, ON

Contributing Author

Simon Travis, DPhil FRCP

Professor of Clinical Gastroenterology,

Kennedy Institute and Translational Gastroenterology Unit,

University of Oxford,

Oxford, UK

Mentoring in IBD Curriculum Steering Committee

Alain Bitton, MD FRCPC, McGill University, Montreal, QC

Karen I. Kroeker, MD MSc FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Cynthia Seow, MBBS (Hons) MSc FRACP, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Jennifer Stretton, ACNP MN BScN, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON

Eytan Wine, MD PhD FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

IBD Dialogue 2024·Volume 20 is made possible by unrestricted educational grants from…

![]()

![]()

Published by Catrile & Associates Ltd., 167 Floyd Avenue, East York, ON M4J 2H9

(c) Catrile & Associates Ltd., 2023. All rights reserved. None of the contents may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the sponsors, the grantor, or the publisher.