Diet and Nutrition in IBD: Food for thought

Diet and Nutrition in IBD: Food for thought

January 20, 2026

Issue 01

Mentoring in IBD is an innovative and successful educational program for Canadian gastroenterologists that includes an annual national meeting, regional satellites in both official languages, www.mentoringinibd.com, an educational newsletter series, and regular electronic communications answering key clinical questions with new research. This issue is based on the presentation made by Dr. Maitreyi Raman, at the 26th annual national meeting, Mentoring in IBD XXVI: The Master Class, held in Toronto on November 14, 2025.

Introduction:

The objectives of this presentation were to discuss the nutrition phenotypes to personalize dietary approaches for the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patient, discuss advances in dietary interventions, explore implications and applications of dietary approaches for clinical practice, and discuss future novel directions for dietary sciences as applied to IBD.

Overall, the field is moving towards personalized dietary interventions and identifying nutrition phenotypes. When considering dietary interventions in IBD, gastroenterologists must ask themselves what they are hoping diet will accomplish for each patient. The goals of dietary interventions can include improvement of malnutrition/sarcopenia, induction of remission, maintenance of remission, disease prevention, rehabilitation/improved surgical outcomes, or improvement in overweight/obesity-induced immune and metabolic dysregulation.

Malnutrition and Sarcopenia

Malnutrition is common in hospitalized and outpatient settings among individuals with IBD, with 45% meeting the criteria for moderate or severe malnutrition.1 Additionally, over 40% of people with IBD experience myopenia (sarcopenia and functional muscle loss).2,3 There are many driving factors among patients with IBD that contribute to malnutrition and sarcopenia. At the forefront is reduced oral intake, whereby patients adopt restrictive or exclusion diets, often without medical supervision. Other factors that may exacerbate the risk include gastrointestinal symptoms, bowel obstruction, hospital procedures, prolonged NPO (nothing by mouth) states, active inflammation due to IBD, high losses through enterocutaneous fistulas and high output from other reasons, and extensive surgical resections.4

Malnutrition in IBD is important to identify as complications include increased infections (pulmonary, wound infection, abscess, urinary tract infection), increased length of stay and hospital readmission rates, wound breakdown, delayed wound healing, leakage or bleeding at the surgical site, cardiac and respiratory insufficiency, compromised bone health, decreased effectiveness of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFa) agents, decreased function, and decreased quality of life.4

Diet and IBD Prevention

Prevention is an important consideration for IBD, as recent data from Crohn’s and Colitis Canada showed that IBD is on the rise in Canada, with a diagnosis every 48 minutes in 2023, expected to increase over the next decade.5 The rising incidence of IBD is a global phenomenon driven in part by urbanization, modernization and the Western diet.6

Studies have investigated the impact of diet on IBD risk. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis explored the relationship between diet and IBD risk. The review included a total of 2,043,601 subjects (62.3% women, mean age 53.1 years) with a mean follow up of 12.8 years. Overall, 1,902 participants developed Crohn’s disease (CD) and 4,617 developed ulcerative colitis (UC). High fiber intake (pooled adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] 0.53, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.41–0.70), Mediterranean diet (pooled aHR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.43–0.81), healthy diets (pooled aHR 0.70, 95% CI: 0.54–0.91), and unprocessed or minimally processed foods (pooled aHR 0.71, 95% CI: 0.53–0.94) were associated with a lower risk of incident CD. In accordance, inflammatory diets (pooled aHR 1.63, 95% CI: 1.26–2.11) and ultra-processed foods (pooled aHR 1.71, 95% CI: 1.36–2.14) were associated with an increased risk of CD.7

Looking at the Mediterranean-like diet specifically, the GEM Study included 2,289 healthy first-degree relatives of patients with CD that were identified and categorized as either having a Mediterranean-like diet or non-Mediterranean-like diet. The group who followed a Mediterranean-like dietary pattern were found to have altered microbiome composition, specifically decreasing Ruminococcus and Dorea, and increasing abundance of Faecalibacterium. The bacterial changes were associated with decreased subclinical gut inflammation in the Mediterranean-like group compared to the non-Mediterranean-like group. No significant associations were found between individual food items and fecal calprotectin (FCP), suggesting that long-term dietary patterns rather than individual food items contribute to or protect against subclinical gut inflammation.8

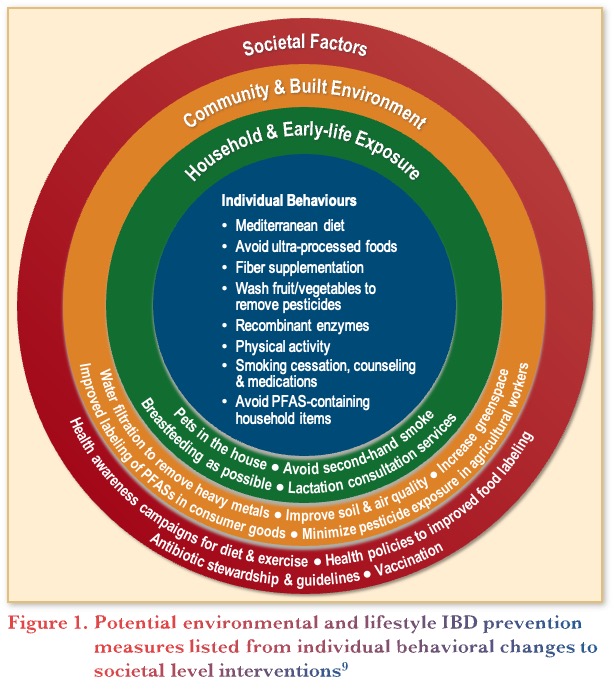

In addition to diet, studies have investigated potential environmental and lifestyle IBD prevention measures, from an individual level to a societal level. Figure 1 outlines interventions for IBD prevention at the various levels, from individual dietary behaviours to societal changes like better food labelling, soil quality, and reduced use of pesticides.9

Diet as IBD Treatment: Induction & Remission

The IBD diet revolution has arrived! Although studies are limited, there are randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that support the use of exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) and partial enteral nutrition (PEN) in IBD. Furthermore, the 2024 American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Clinical Practice Update on diet and nutritional therapies in IBD made specific recommendations for the use of EEN for induction of clinical remission and endoscopic response in CD, particularly in children. They noted that EEN may also be an effective therapy in malnourished patients before undergoing elective surgery for CD to optimize nutritional status and reduce postoperative complications. The CD exclusion diet (CDED), a type of PEN, was also considered an effective therapy for induction of clinical remission and endoscopic response in mild-to-moderate CD of relatively short duration in the AGA Practice Update.10

Rationales for the diet revolution in IBD include incomplete response and remission rates from current immune-based therapies, with 30-40% primary nonresponse and up to 40% secondary loss of response rates despite new advanced therapeutic options. In addition, diet leverages different mechanisms of action, there is increased patient awareness and demand for dietary interventions, and importantly, the data support dietary approaches to treatment.11,12

Therapeutic Diets

There are a range of evidence-based therapeutic diets studied in IBD, including CDED with PEN, the Tasty and Healthy diet, the Mediterranean diet, the Specific Carbohydrate Diet, IBD Autoimmune Diet, and the IBD Food Pyramid as a few examples. The use of these diets needs to be individualized to each patient’s goals and lifestyle, while considering disease related factors such as induction of remission or maintenance, food literacy, financial limitations, and involvement of the care team.

The most extensive data exist for the use of CDED + PEN, based on 15 clinical studies (including 4 RCTs and 5 studies focused on adults). Overall, the data demonstrated that CDED + PEN is associated with improved tolerance compared to EEN and induction of clinical remission.13 In one study by Sigall-Bonet and colleagues,14 after 6-weeks of CDED + PEN, 70% of children and young adults with mild-to-moderate CD experienced clinical remission and C-reactive protein (CRP) normalization. In a follow-up study among children who achieved remission with CDED + PEN or EEN, 80% achieved sustained remission by week 3. These data suggest that a dietary-responsive phenotype can be identified early in the course of therapy and support the usefulness of dietary changes. Furthermore, superior responses (significant reductions in FCP and improved albumin) have been seen in biologic-naïve adults compared to those with previous loss of response to biologics.15

With respect to other therapeutic dietary interventions, a recent multicentre RCT compared the Tasty & Healthy Whole Foods Diet vs. EEN for 8 weeks. Results showed superior tolerability of the Tasty & Healthy diet (88% vs. 52%; p<0.001) and a non-significant trend towards superior symptomatic remission (56% vs. 38%). Objective markers of disease activity (calprotectin, CRP, erythrocyte sedimentation rate) improved similarly in both groups. In addition, the Tasty & Healthy diet increased microbiome diversity and decreased pro-inflammatory species, while EEN decreased microbiome diversity.16 Looking at IBD-MAID (modified anti-inflammatory diet), a recent RCT in adults investigated the impact in active UC or CD. Results showed that IBD-MAID was both well-tolerated and well-adhered to (92% adherence), while demonstrating statistically significant improvements in symptoms (p=0.001), quality of life (p=0.004), FCP (p=0.007), and CD activity (p=0.03) at week 8, but no significant impact in UC.17

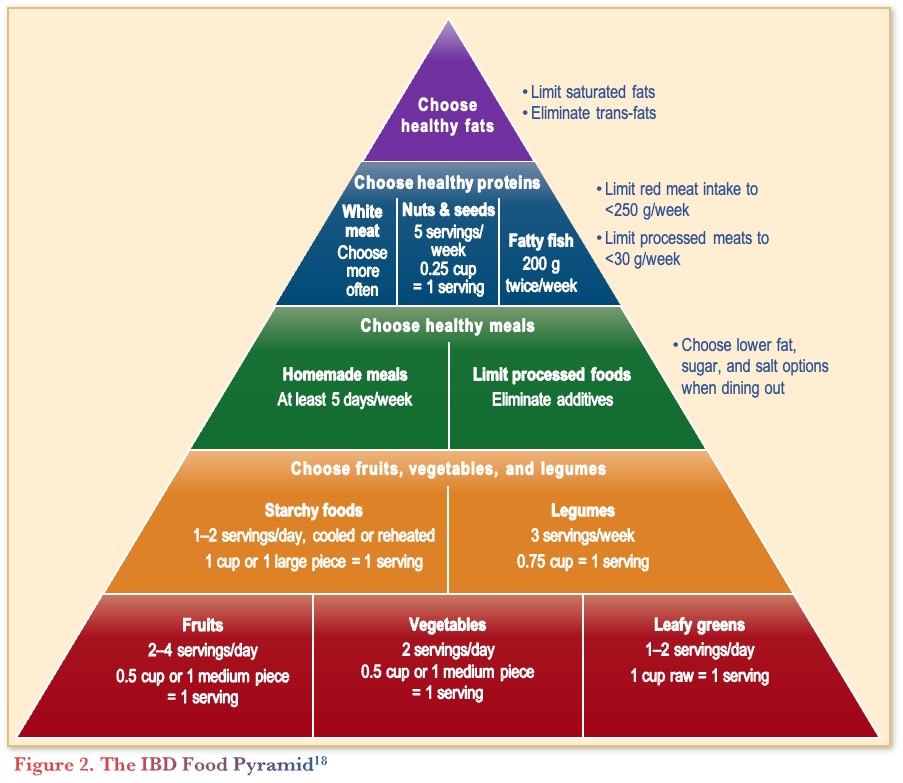

In terms of the guidelines, the 2024 AGA Practice Update on diet and nutritional therapies in IBD recommends all patients with IBD follow a Mediterranean diet (unless contraindicated).10 Figure 2 depicts the IBD Food Pyramid, a modification of the Mediterranean diet, that prioritizes food and food components that are mechanistically associated with better inflammatory responses in patients with IBD.

A preliminary unpublished study of a therapeutic diet intervention in CD (CD-TDI) based on the IBD Food Pyramid compared a structured whole-food diet with a habitual diet in patients with mild to moderately active CD over 13 weeks (n=64). The study found that patients receiving the CD-TDI diet had a significant reduction in clinical activity (Harvey-Bradshaw Index) compared to baseline (p=0.0327), FCP (p=0.0341), and CRP (p=0.0254), supporting an anti-inflammatory effect of the diet.19

Thus overall, recent studies of therapeutic diets in IBD have demonstrated both improved clinical symptoms and objective inflammatory markers, providing evidence supporting the use of these diets alongside standard care for CD.

Future Directions

Current research aims to provide patients with personalized nutrition based on biological signatures including genetics, the microbiome, and multi-omics. Qualitative methods of assessing dietary intake (e.g., food frequency questionnaires, 24-hour food recalls) have limitations, so avenues to evaluate dietary intake objectively are appealing. For example, Diener and colleagues20 were able to accurately characterize over 400 foods using stool metagenomics to sequence food DNA with comparable or even superior outcomes to dietary data obtained through standard of care food records and survey-based questionnaires. Findings suggest that future studies may be able to use food-based DNA for diet assessments and integrate findings into microbiome research, but validation studies are needed.

In an effort to investigate the ability of predicting response to dietary interventions, Raman and her colleagues19 used three UC cohorts that have undergone a dietary intervention to develop a predictive model of FCP response. Food-based survey data, food DNA from stool samples, stool metabolites, and stool gut microbial taxa were collected at baseline. Using these data, they were able to predict response to the dietary intervention (based on FCP) by using stool DNA and stool metagenomics, suggesting the potential to personalize dietary interventions as these models are further validated.

Lastly, one of the most exciting frontiers in IBD nutrition is the use of artificial intelligence (AI) models integrating diet, microbiome, genetics, and clinical data to provide precision nutrition recommendations. By predicting who will respond to certain dietary therapies, or which foods may drive inflammation in an individual patient, personalized medicine can be applied similarly to what is being investigated in other therapeutic areas.21

Conclusions

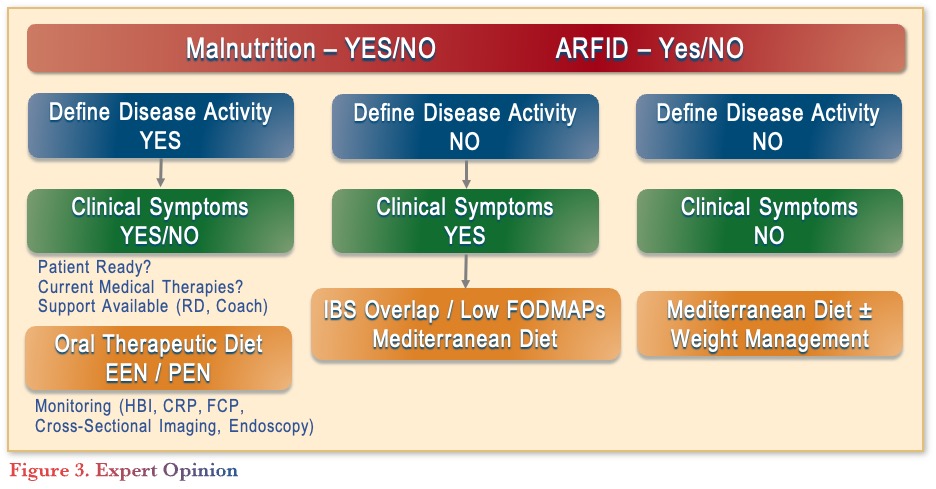

In conclusion, screening for malnutrition is an essential component of IBD care, as diet can play a critical role in IBD prevention and treatment. Prior to recommending any diets, patients should be screened for malnutrition or ARFID (avoidant restrictive food intake disorder) and have their disease activities defined with symptom characterization (see Figure 3). Depending on the disease activity and clinical symptoms, various diets can be recommended, considering patient readiness, medical therapies, and support systems. As future research evolves, there is potential for personalization of treatment through food DNA sequencing and AI.

Clinical Case

Joanna is a 23-year-old Master’s student who you are meeting for the first time following her CD diagnosis last week. She has moderately severe ileocolonic inflammatory disease with elevated stool and serum markers.

She was previously healthy but over the last few months developed abdominal pain and diarrhea. She has eaten very little for 5-6 weeks, losing 7% of her body weight. She previously had a body mass index (BMI) of 31 kg/m2 and was not a ‘healthy eater’.

Commentary

- When a patient like Joanna asks if her CD is because of her poor diet, most gastroenterologists would respond that it is hard to conclude on an individual basis that what a person eats causes the disease, but eating healthy is always recommended.

Case Evolution

On physical exam, she appears pale and fatigued and has angular cheilitis. Her labs show a low albumin of 27 g/L and a hemoglobin of 103 g/L, along with low iron, vitamin D, and vitamin B12. She has a CRP of 33.2 mg/L and fecal calprotectin of 1,202 µg/g.

You discuss a treatment plan with her and suggest starting prednisone with a plan to initiate an anti-IL-23 monoclonal antibody (mAb).

The medical student with you in the clinic asks whether the weight loss and abnormal nutrition lab results are a problem that needs to be addressed or whether they are ‘just part of having CD’.

Commentary

- Most gastroenterologists would explain that nutritional assessment is an integral part of evaluating any new patient with IBD.

- When considering implementing dietary interventions, it is recommended to collaborate with a dietitian to help with patient education, engagement, and adherence.

Case Evolution

You decide to refer Joanna to a dietitian since you do not know much about diet in IBD (you had COVID when the lecture on diet in IBD was given during your gastroenterology fellowship).

Joanna tells you that she heard in her graduate class that diet and microbes might be important in multiple sclerosis (MS; she works on animal models of MS) and wonders if the same is true for IBD. She asks whether any specific diets can be used to treat her CD, either alone or with the other therapies you discussed.

Commentary

- For induction of remission, most gastroenterologists would explain to Joanna that diet therapy can be used as monotherapy or in combination with other treatments.

- Patients, particularly with mild to moderate disease severity, may adopt restrictive diets to manage symptoms, but these approaches may not target inflammation resolution. Adopting a therapeutic diet supervised by a dietician may improve diet and nutrition quality along with the mechanisms driving disease pathogenesis.

- Phone applications can be helpful in supporting patients with dietary assessment and adherence.

Case Evolution

Joanna decides to take prednisone but also starts the CDED. Determined to do anything she can to control her inflammation, she starts anti-IL-23 therapy two weeks later and stops the prednisone, as you feel that the addition of diet therapy provides the opportunity to significantly reduce her steroid exposure. She goes into remission quickly, which is maintained with her biologic and modified exclusion diet that she develops based on her experience with the guidance of an experienced IBD dietitian.

Upon follow-up 3 years later, Joanna is in prolonged remission following the same treatment course (CDED principles and anti-IL-23 therapy). She tells you she is planning on having children and wants to know how she can minimize the risk of her child developing IBD.

Commentary

- For preventing IBD in her child, the majority of gastroenterologists would explain that breastfeeding is the nutritional intervention with the best evidence for preventing development of IBD.

References

-

- Allard JP, Keller H, Jeejeebhoy KN, et al. Malnutrition at hospital admission—contributors and effect on length of stay. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2015;40(4):487–97.

- Hollingworth TW, Oke SM, Patel H, Smith TR. Getting to grips with sarcopenia: recent advances and practical management for the gastroenterologist. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2020;12(1):53–61.

- Ryan E, McNicholas D, Creavin B, et al. Sarcopenia and inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;25(1):67–73.

- Chiu E, Oleynick C, Raman M, Bielawska B. Optimizing inpatient nutrition care of adult patients with inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century. Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1581.

- Coward S, Benchimol EI, Kuenzig ME, et al. The 2023 impact of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: epidemiology of IBD. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023;6(Suppl_2):S9–15.

- Hracs L, Windsor JW, Gorospe J, et al. Global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease across epidemiologic stages. Nature. 2025;642:458–66.

- Meyer A, Agrawal M, Savin-Shalom E, et al. Impact of diet on inflammatory bowel disease risk: systematic review, meta-analyses and implications for prevention. EClinicalMedicine. 2025;86:103353.

- Turpin W, Dong M, Sasson G, et al. Mediterranean-like dietary pattern associations with gut microbiome composition and subclinical gastrointestinal inflammation. Gastroenterol. 2022;163(3):685–98.

- Lee SH, Lopes E, Colombel JF, Ungaro R. Identifying potential targets for the interception of inflammatory bowel disease: toward precision prevention. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025;31(Suppl_2):S51–60.

- Hashash JG, Elkins J, Lewis JD, Binion DG. AGA clinical practice update on diet and nutritional therapies in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: expert review. Gastroenterol. 2024;166(3):521–32.

- Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al. STRIDE-II: an update on the selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE) initiative of the international organization for the study of IBD (IOIBD): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterol. 2021;160(5):1570–83.

- Kennedy NA, Heap GA, Green HD, et al. Predictors of anti-TNF treatment failure in anti-TNF-naive patients with active luminal Crohn’s disease: a prospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(5):341–53

- Boneh RS, Westoby C, Oseran I, et al. The Crohn’s disease exclusion diet: a comprehensive review of evidence, implementation strategies, practical guidance, and future directions. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;30(10):1888–902.

- Sigall-Boneh R, Pfeffer-Gik T, Segal I, et al. Partial enteral nutrition with a Crohnʼs disease exclusion diet is effective for induction of remission in children and young adults with Crohnʼs disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(8):1353–60.

- Jijón Andrade MC, Muncunill GP, Ruf AL, et al. Efficacy of Crohn’s disease exclusion diet in treatment-naïve children and children progressed on biological therapy: a retrospective chart review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23(1):225.

- Frutkoff YA, Plotkin L, Pollak D, et al. Whole food diet induces remission in children and young adults with mild to moderate Crohn’s disease and is more tolerable than exclusive enteral nutrition: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterol. 2025;169(7):1462–74.e2.

- Marsh A, Chachay V, Banks M, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial investigating the effects of an anti-inflammatory dietary pattern on disease activity, symptoms and microbiota profile in adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2024;78(12):1072–81.

- Sasson AN, Ingram RJM, Zhang Z, et al. The role of precision nutrition in the modulation of microbial composition and function in people with inflammatory bowel disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(9):754–69.

- Raman M. Unpublished data presented at MIIBD XXVI on November 14, 2025, in Toronto, ON.

- Diener C, Holscher HD, Filek K, et al. Metagenomic estimation of dietary intake from human stool. Nat Metab. 2025;7(3):617–30.

- Baldi S, Sarikaya D, Lotti S, et al. From traditional to artificial intelligence-driven approaches: Revolutionizing personalized and precision nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2025;68:106–17

Editor-in-Chief

John K. Marshall, MD MSc FRCPC CAGF AGAF

Professor, Department of Medicine

Director, Division of Gastroenterology

McMaster University

Hamilton, ONContributing Author

Maitreyi Raman, MD MSC FRCPC

Associate Professor of Medicine

Cumming School of Medicine

University of Calgary

Calgary, AB

Mentoring in IBD Curriculum Steering Committee

Alain Bitton, MD FRCPC, McGill University, Montreal, QC

Karen I. Kroeker, MD MSc FRCPC, University of Alberta, Edmonton, AB

Cynthia Seow, MBBS (Hons) MSc FRACP, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB

Jennifer Stretton, ACNP MN BScN, St. Joseph’s Healthcare, Hamilton, ON

Eytan Wine, MD PhD, FRCPC, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON

IBD Dialogue 2026·Volume 22 is made possible by unrestricted educational grants from…

Published by Kalendar Inc., 7 Haddon Avenue, Scarboro, ON M1N 2K7

© Kalendar Inc. 2026. All rights reserved. None of the contents may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the publisher. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or recommendations of the sponsors, the grantor, or the publisher.